Artificial intelligence and robotics are currently undergoing constant transformation. The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and Columbia University have presented a system based on computer vision algorithms and machine learning. It is called Tool-as-interface and learns through observation, like the astronauts on the Apollo mission. Generative AI is the model for efficient learning. Read on to find out more.

The fascination with robots

Robots have always fascinated us with their ability to perform repetitive tasks with precision. But outside of factories, their performance is clumsier than we tend to think: most cannot adapt to unforeseen situations. If the camera moves, if the environment changes, or if the object is not exactly where it should be, they freeze. In contrast, a person cooking can use the same pan to fry, stir, or flip an egg without thinking too much about it. The difference is that humans learn by watching and practicing, not by following rigid instructions.

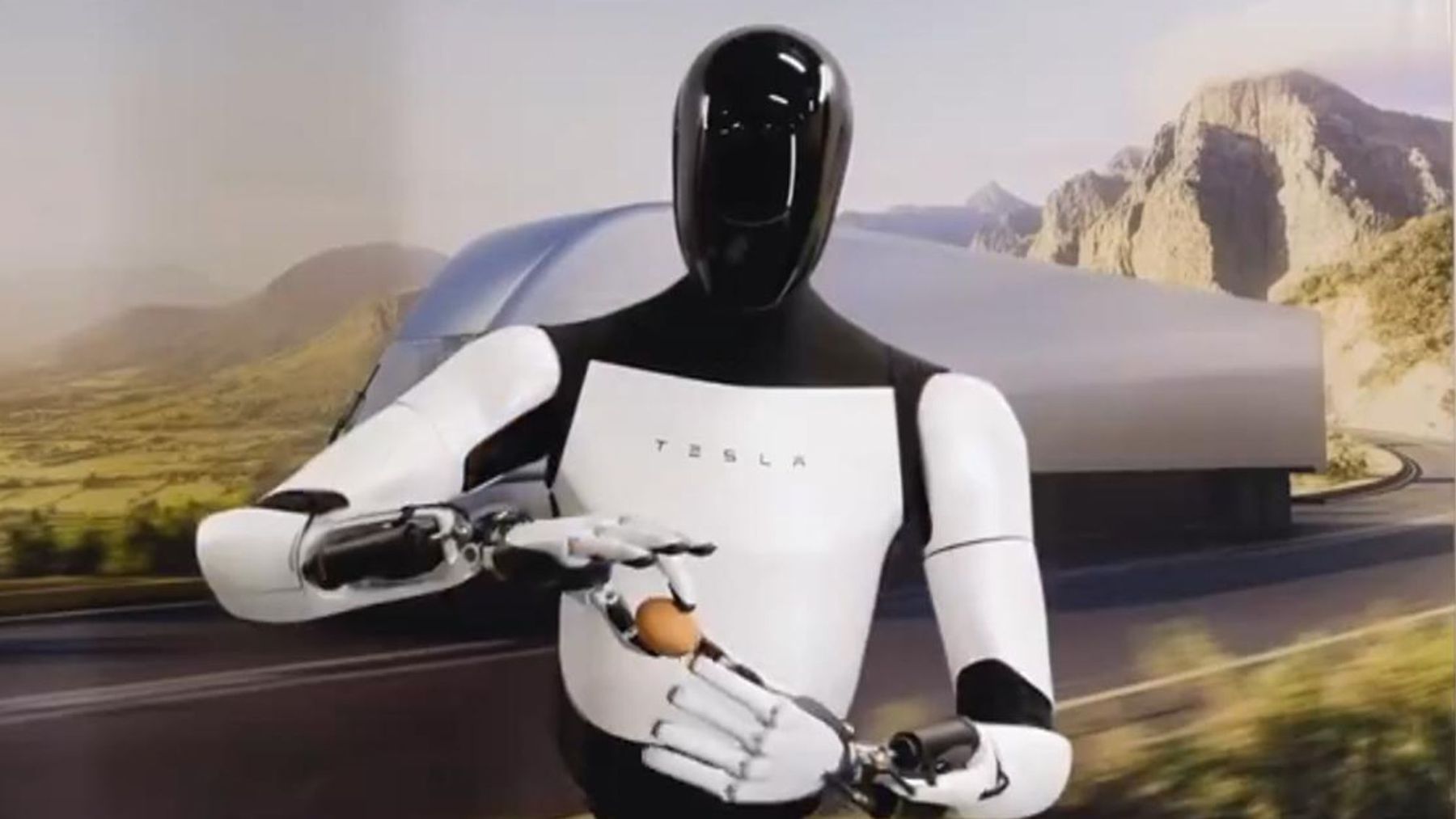

This principle inspired a group of researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, in collaboration with Columbia University. In their work, they show that a robot was able to flip an egg in a frying pan, hammer a nail, or balance a bottle of wine simply by watching videos of people performing these tasks. There was no need to program each movement or control it with a joystick. As the authors write in the article: “Our framework allows for the direct transfer of human gameplay data into deployable robotic policies.”

How the “tool as interface” idea works

The team calls their approach Tool-as-Interface, because it emphasizes the tool being used (a frying pan, a hammer, a spoon) rather than the human hand manipulating it. The key is that the robot does not try to copy the person’s gestures, but rather learns the trajectory and orientation of the object. This way, it does not matter if the human arm and the robot arm are different, because they both share the tool as a common point.

To train the robot, simply record the action from two cameras. These two angles allow the scene to be reconstructed in 3D using a vision model called MASt3R. Then, another technique called 3D Gaussian splatting generates additional views of the same moment, so that the robot can “see” the task from different angles. Thus, even if the camera moves during execution, the system remains stable. No expensive sensors or controlled environments are required.

The decisive step: removing humans from the video

A key detail is that the algorithms remove the human hand from the recorded material. With the help of the Grounded-SAM model, everything corresponding to the human body is segmented and masked. What remains in the video is only the tool interacting with the objects. This way, the robot learns by observing what the frying pan, hammer, or spoon does, rather than how the person’s fingers move.

This solves what the authors call the “embodiment gap”: the fact that humans and robots have very different morphologies. As they explain in the article, “abstracting actions to the tool frame reduces morphological dependency, allowing policies to be generalized across embodiments.” In practice, this means that the same dataset can be used to train robotic arms with six or seven degrees of freedom, without having to repeat the entire process.

Tests with nails, meatballs, and eggs

The experiments included five tasks that require speed, precision, or adaptability. Among them: hammering a plastic nail, removing a meatball from a frying pan with a spoon, flipping an egg in the air using a frying pan, balancing a bottle of wine on an unstable stand, and kicking a ball with a robotic golf club.

What is remarkable is that many of these actions are impossible to capture with classic teleoperation methods because they are too fast or unpredictable. In the frying pan test, for example, the robot was able to flip an egg in just 1.5 seconds. In the meatball test, it continued to perform correctly even when a human added more balls to the pan in the middle of the process. The system was not thrown off balance; it simply adapted.

Results compared to traditional methods

The researchers compared their approach with other systems such as teleoperation with specialized joysticks or the use of 3D-printed manual grippers. The difference was enormous: the success rate increased by 71% compared to policies trained with teleoperation, and data collection time was reduced by 77%. In addition, the technique proved robust even when the camera was shaking or when the robot’s base was moving.

In more concrete terms, in the task of hammering a nail, the classic methods failed in all 13 attempts, while with Tool-as-Interface, the robot succeeded all 13 times. In the task of cracking an egg, the previous systems could not even complete it, while the new framework achieved 12 successful attempts. It is a qualitative leap in the way robots are trained.

Beyond the laboratory: what does this mean?

The team emphasizes that this breakthrough opens the door to training robots with home videos recorded on cell phones. Today, there are more than 7 billion cameras of this type in the world, turning every kitchen, workshop, or warehouse into a potential learning environment. If the algorithms are perfected, a robot could learn to cut vegetables, use a screwdriver, or fold clothes by watching clips recorded by anyone.

In the words of the authors: “Our approach eliminates the need to design, print, or manufacture additional hardware during data collection, ensuring a cost-effective and inclusive solution.” This accessibility is what sets Tool-as-Interface apart from other more expensive and exclusive methods.

Limitations and future challenges

The system still has weaknesses. For starters, it assumes that the tool is firmly attached to the end of the robotic arm, which is not always the case in real life. It also relies on a pose estimation model that can make mistakes, and the synthetic camera angles generated sometimes lack realism. Another challenge is that it currently only works well with rigid tools; the method needs to be extended to flexible or soft objects.

The researchers themselves acknowledge that “improving the reliability of the perception system through more robust pose estimation algorithms is a promising direction for the future.” They also plan to explore representations that allow working with deformable tools, such as sponges or soft tweezers.