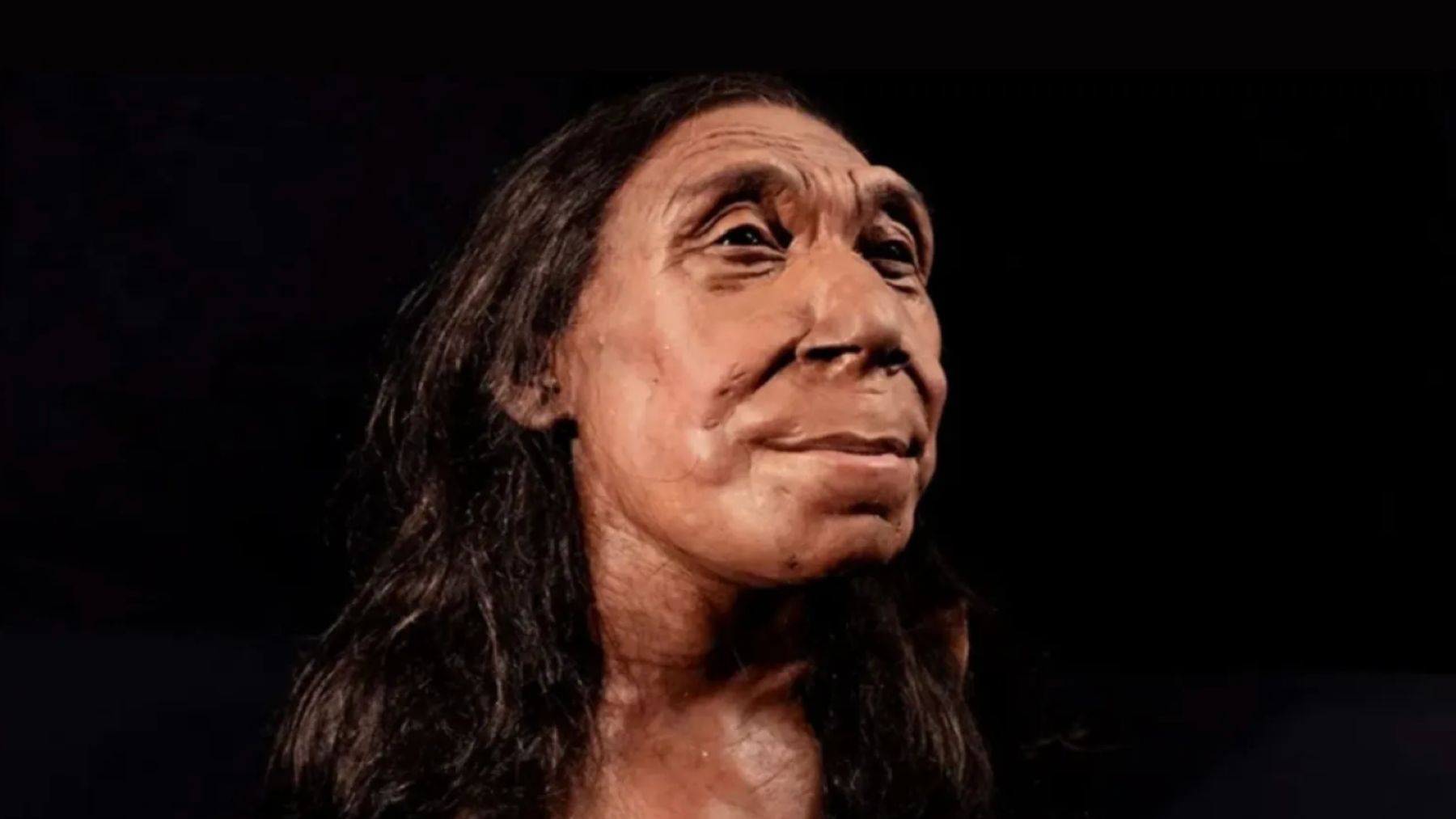

Some of the secrets of ancient times are held by humans. In a cave in Kurdistan, they found Shanidar Z, the name given to the remains of a woman who lived 75,000 years ago and died at the age of 45, a very advanced age for her time. The image of her face, reconstructed using technology, has revealed compassion, collective memory, and a profound shared humanity. In other words, Neanderthals were not the brutish creatures that had been assumed.

The reconstructed figure, “Shanidar Z,” is in honor of the cave where it was found

We go back in time to 2018, when a team of archaeologists led by the University of Cambridge discovered the remains of a female Neanderthal during excavations inside a cave in Iraqi Kurdistan. The reconstructed figure, “Shanidar Z,” is in honor of the cave where it was found. But beyond the name, this discovery puts a face to a past we can now look directly into. Shanidar Cave had already become famous in the late 1950s, when archaeological work uncovered the skeletal remains of several Neanderthals who had been buried there. In this case, the recovery of a crushed skull, preserved in the sediment for millennia, was enough to recreate the humans of that time.

Shanidar Z’s facial reconstruction shows a mature woman, with a strong face and defined features, with an air of familiarity

As we mentioned, in the 1950s, American archaeologist Ralph Solecki had already unearthed the remains of at least ten Neanderthals there. On that occasion, the discovery of the remains led to the discovery that one of them showed signs of having lived with severe disabilities, which led to the first suggestion that this species cared for its own. Now, Shanidar Z’s facial reconstruction shows a mature woman, with a strong face and defined features, with an air of familiarity that is hard to ignore. The reconstruction shows a face that seems familiar.

Neanderthal skulls have enormous brow ridges and lack chins, with a projecting midface that results in more prominent noses

This reconstruction was made possible thanks to a collaboration with brothers Adrie and Alfons Kennis, renowned Dutch paleoartists specializing in the anatomical recreation of hominids from skeletal remains. “Neanderthal and human skulls look very different. Neanderthal skulls have enormous brow ridges and lack chins, with a projecting midface that results in more prominent noses. But the recreated face suggests that these differences were not so marked in life,” says Emma Pomeroy, a paleoanthropologist at the Department of Archaeology at the University of Cambridge.

Emma Pomeroy: “It was like a high-stakes 3D puzzle. A single block needed about 15 days to process”

There are many clues in this research that lead to the same conclusion. Neanderthals cared for each other and were not grotesque beings. The teeth, worn down to the roots, reveal that she probably died around 40 or 45 years old, an advanced age for her time. “It was like a high-stakes 3D puzzle. A single block needed about 15 days to process,” Pomeroy explained about the delicate reconstruction process. In fact, thanks to the reconstruction and preservation process, signs of oral infections and gum disease have even been detected, suggesting a final stage of life marked by physical decline. Even so, she survived long enough to grow old, implying that she lived in a caring community.

This discovery demonstrates how many unknowns remain about how the world inhabited by humans functioned millennia ago. It also demonstrates that the sense of humanity already existed even when humans were more animal than human. “Perhaps it’s easier to see how interbreeding occurred among our species, to the point that almost all humans alive today still have Neanderthal DNA,” the paleontologist said.