Michelangelo’s paintings that decorate the Sistine Chapel are one of the greatest achievements of Renaissance art and one of the world’s top tourist destinations. Commissioned by Pope Julius II between 1508 and 1512, these works transformed the conception of frescoes in the history of Western art. The monumentality of the figures, the innovative composition, and the anatomical mastery make these frescoes an inescapable reference. More than 500 years after its creation, Michelangelo’s masterpiece continues to surprise us with details that have gone unnoticed or ignored.

This is the reason why Michelangelo painted God’s bottom on the Sistine Chapel

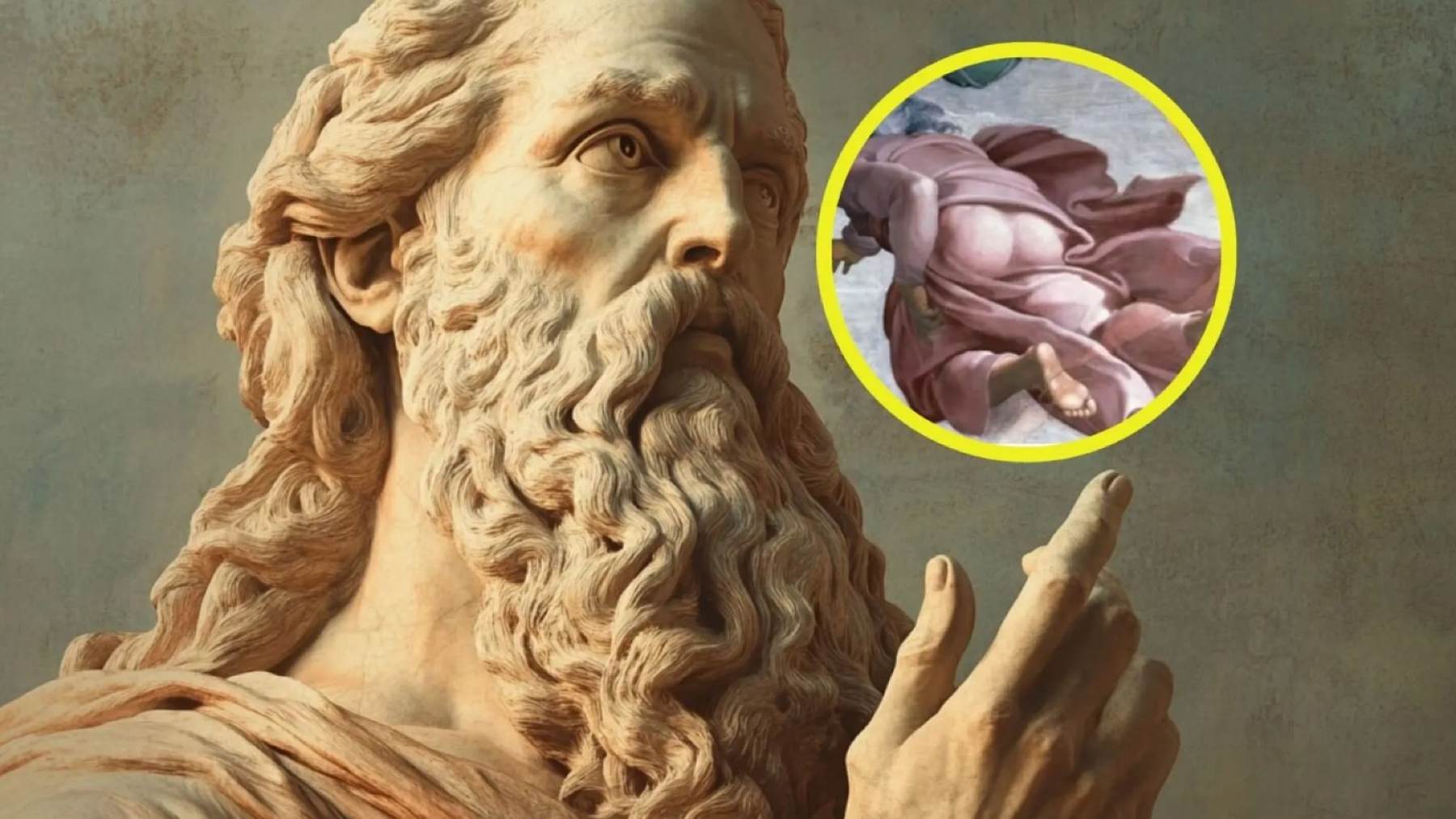

While the most famous paintings of the pictorial ensemble are The Creation of Adam and The Last Judgment, one particular detail has lately come to light: the depiction of God’s posterior in one of the vault scenes. This discovery has prompted several speculations regarding the meaning of this strange iconography and Michelangelo’s aims. In the upper part of the Sistine Chapel’s vault, the scene of The Separation of Light from Darkness depicts God’s bottom. In this composition, God is portrayed on his back, with a floating garment covering the lower portion of his torso, exposing his buttocks. After being overlooked for centuries, this information has now come to light, leading to new research directions on how divinity is portrayed in Renaissance art.

The holy figure’s pose, which features the torso turned and the lower body twisted, demonstrates Michelangelo’s skill at depicting movement and human anatomy. God’s distinctive long beard and roomy clothes are depicted in The Separation of Light from Darkness in the Sistine Chapel. Raising his hands to separate the light from the darkness, he exudes a majestic and commanding demeanor. However, the way Michelangelo portrayed the heavenly body—which we can see from an angle that exposes his partially veiled backside—sets this portrayal apart from others that are comparable. This unique perspective emphasizes the composition’s three-dimensionality and God’s bodily presence. This symbolic choice could be understood theologically as a confirmation of the divinity’s humanity, consistent with Neoplatonic ideas that shaped the Renaissance.

The Renaissance’s views on male nudity and buttocks

Classical Greco-Roman sculpture served as an inspiration for the Renaissance’s renewed interest in human anatomy. During this time, male nudity was regarded by artists as the pinnacle of beauty and anatomical perfection. In their works, artists like Donatello, Leonardo da Vinci, and Raphael investigated anatomy with a nearly scientific fascination, depicting nude bodies. Male buttocks were portrayed in this context as a means of showcasing expressiveness and technical proficiency rather than as a taboo subject.

Michelangelo’s murals of the Battle of Cascina and Donatello’s David are notable examples, both of which feature a preponderance of nude male bodies. Sculptures like David and The Dying Slaves demonstrate Michelangelo’s well-known interest in the male form. He also pays close attention to the naked in his frescoes. In the Last Judgment, for instance, the entire area is filled with the nude bodies of the blessed and the condemned. In addition to its visual value, the male posterior frequently appears in his artwork because of its symbolic meaning. For instance, the soldiers’ different positions during the Battle of Cascina highlight this particular body area. A long-standing artistic tradition that associates the buttocks with physical strength and vigor is addressed by this motif.

Furthermore, Michelangelo’s masterpiece can be viewed from a different angle thanks to the Sistine Chapel’s artistic focus on the backside of God. The concept that the artist wanted to explore the boundaries of human anatomy and spatial composition in addition to representing the divine is further supported by this detail. Beyond its seeming anecdotal nature, this conclusion emphasizes how crucial it is to thoroughly examine the great works of the past. Unexpected subtleties might surface in a work as closely examined as the Sistine Chapel, leading to new research directions. Michelangelo’s genius and unmatched artistic vision are further demonstrated by the Sistine Chapel’s depiction of heavenly bottoms.